Change of address fraud can have lasting fallout, but USPS won’t say how it plans to close the loophole

Like tens of millions of Americans do every year to redirect their mail to a new address, someone went into a U.S. post office and completed a change of address form. After completing the paperwork and turning it in, the individual left USPS address change. That was sufficient to start a chain reaction that turned the life of a former Microsoft executive into a nightmare several states away, since the individual who signed the form within minutes effectively took control of the executive’s home address.

A basic weakness in the way the U.S. Postal Service handles address changes is the basis for this fraud. Neither fraudsters nor federal investigators are particularly familiar with this strategy, nor is it novel. For the thousands of people whose mail is stolen and redirected each year, a fraudulently filed change of address form can have long-lasting consequences. Criminals can gain bills, credit cards, and other sensitive information that can be used to break into bank accounts or make fraudulent transactions.

Even more puzzling is the apparent equally straightforward solution. Although USPS admits that there is an issue, it does not specify how it intends to close the gap that lets identity thieves profit from the theft of others.

The ex-Microsoft executive, who consented to share his tale with TanzoHub but wished to remain anonymous, is aware of the risks to cybersecurity and privacy. However, the former executive freely acknowledged that he had no idea it was so simple for someone to change his address intentionally without his permission, let alone provide an opportunity for thieves to rob his accounts and maybe make thousands of dollars’ worth of fraudulent purchases. He claims that all of this is the result of a straightforward paper form that is mindlessly sent to the post office.

In 2021, the USPS handled about 36 million address changes. A change of address can be made in two ways. The majority of customers pay $1.10 for expedited convenience after completing the form online and entering both their old and new addresses. The alternative is to complete the paper form at your neighborhood USPS post office, which is still utilized by a sizable minority of people.

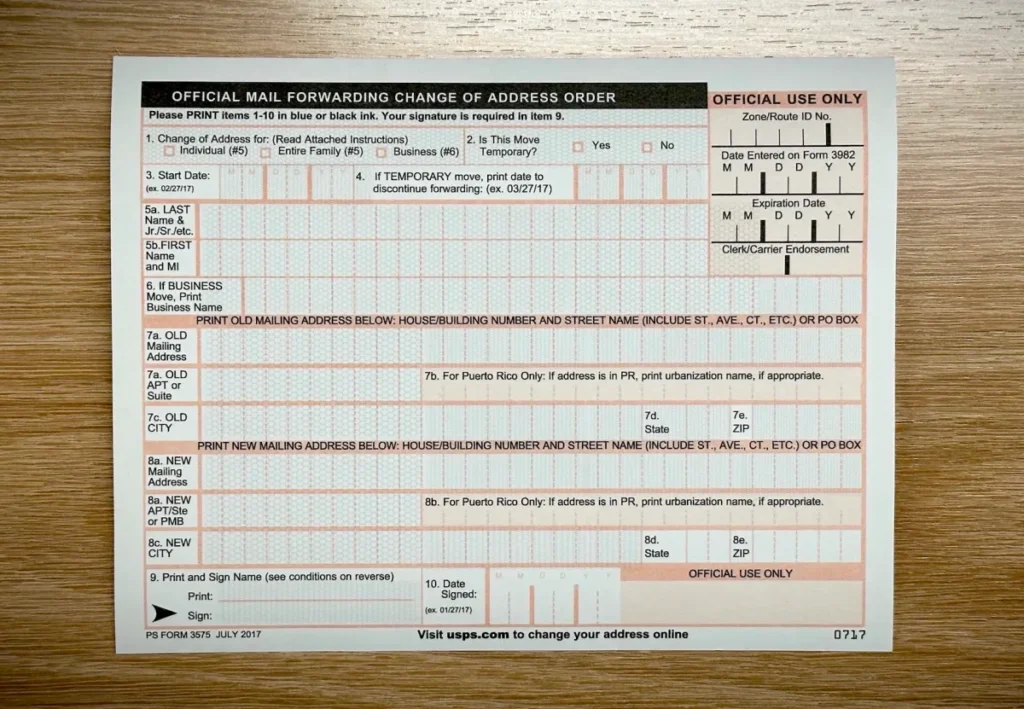

The individual is not required to provide identification while completing an online or paper form. Even while the online form, at the very least, costs a little money and doesn’t in any way verify someone’s identity, it creates a digital paper trail that can be eventually linked to an individual. However, USPS mostly depends on the system accepting the identity of the individual signing the paper form.

PS Form 3575 is the official name of the paper form. This form, as complex as government paperwork gets, is incredibly bland and refreshingly easy. The postcard-sized form is only available for request at a USPS post office, which is what we did for journalism! After that, the person fills it out with their name, new address, old address, and the duration of the mail redirection.

The final step is to sign the form, return it to a postal worker, or place it in the post office’s letter mail slot. However, there is no assurance that USPS will verify the identity of the individual submitting a paper change of address form, save from a notice on the back alerting the recipient to the possibility of criminal charges (if discovered). That is the basic weakness that scammers take advantage of to obtain victims’ home addresses, credit cards, and bank accounts.

USPS notifies the resident that their address change was successful by sending two letters—one to the old address and one to the new address—after a form is turned in and processed. However, it is easy for people to overlook these letters, and they only need to be viewed or cancelled if the recipient wishes to “view or cancel” an unauthorized change of address request.

This defect is not only well known, but it is also not brand-new. In a particularly hilarious case from 2017, an Atlanta homeowner was jailed for cashing cheques that he had fraudulently redirected from UPS’s corporate headquarters. As a result, the unfortunate fraudster’s flat was surrounded by literal bathtubs of mail. Even still, it took UPS over three months to realize that its mail was missing.

The former CEO provided TanzoHub with a letter from one of his banks, which supports his story and states that the bank updated its systems “because of information received from the United States Postal Service (USPS) indicating that an address change had occurred.” The fake change of address under the former executive’s name was approved by USPS, which then forwarded the new address to numerous other businesses, including his banks. For many years, the USPS has been selling change of address information to data brokers, who then market the information to any interested parties, including financial institutions.

It was fortunate for him that he discovered the scam before the perpetrators could cause permanent harm, but it still took weeks for his accounts and residential address to be restored. However, thousands of people who lack the influence of a former tech CEO are still impacted by change of address fraud each year and are unable to resume their normal lives.

TanzoHub contacted the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) for comment in order to see how it was minimizing this type of change of address fraud, as it is still a problem.

The law enforcement division of the USPS, US Postal Inspection Service, or USPIS, received our email and declined to comment. USPS spokespeople Sue Brennan and Tatiana Roy sent TanzoHub a boilerplate statement that repeated some of itself, but they did not elaborate on how they intended to stop change of address fraud. In spite of the fact that it is customary for reporters to inquire, USPIS consistently refused to give TanzoHub the name of a spokesperson and instead delivered its response from a generic, anonymous email address. Ariana Ramirez of USPIS refuses to divulge the identity of the department’s media spokesman when contacted by email.

“As these situations arise, USPS reevaluates their internal controls to address security concerns,” USPIS said in a boilerplate statement. However, it did not specify which internal controls, if any, or whether any adjustments had been made. We enquired once more, but got no answer.

The letter went on, “Customers are encouraged to monitor the receipt of their mail, by retrieving it daily from their mailbox or through Informed Delivery online,” referring to the online tool that lets locals see what mail and parcels are arriving from the USPS. Though it’s not a guarantee, checking your mailbox on a frequent basis may help you catch lost mail before it’s too late. That’s the reason con artists continue to do it.

What would seem to be an easy remedy was not highlighted by USPS or USPIS. Should the online form necessitate a minor payment to mitigate the possibility of fraudulent activity, why not verify the individual’s identification before submitting the form in person?

The concept is not new. Change of address fraud has long been a source of worry for the USPS Office of Inspector General (USPS OIG), the independent watchdog that monitors the postal service. In its 2018 audit report, the USPS OIG stated that it did not require customers to present a government form of identification, such as a passport or driver’s license, for review when submitting a paper change of address form. The audit was initiated in response to concerns raised by lawmakers, news outlets, and customer complaints. When manually submitting a change of address form, the watchdog observed that a number of foreign postal services, including those in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, require some sort of identity check. However, they also accept a variety of documents from people who do not possess a government-issued form of identification.

USPS Address Change

The USPS OIG’s conclusions were unambiguous. “The absence of a national policy to support such an ID-requirement regulation may encourage further fraud and damage the Postal Service’s reputation as a reliable source.”

In the wake of the audit, USPS announced that by the end of March 2019, paper change of address forms would be subject to government-issued identity verification.

Speaking with TanzoHub , USPS OIG spokesperson Bill Triplett stated that the agency concurred with the inspector general’s conclusions in its 2018 audit report and that the recommendations were closed in August 2019, signifying a resolution of the issue. USPS “provided documentation demonstrating sales associates require identification to process change of address requests in person,” according to the spokeswoman.

The Postal Service would have the most recent information on how they are enforcing their policies, the company said in response to a question regarding whether or not it implements this guideline. The spokesman stated, “Generally, we don’t follow up to see if the Postal Service is still implementing recommendations once we close them based on supporting material they give.

“Consider auditing this topic in the future,” the USPS OIG stated.

To put it plainly, when someone files a paper change of address form, USPS is not sufficiently implementing its own policy on identification checks. USPS has not yet provided a statement or mentioned any initiatives it is taking to lessen this type of fraud.

There are many examples of this than just one unfortunate former Microsoft executive who slipped between the gaps. Just six months prior, Seattle-based KIRO 7 News examined this case and came to the same findings. Following a story on a local family that had experienced this problem twice, USPS discounted the family’s experience, asserting that identity theft “cannot happen” through fraudulent change of address transactions.

However, that doesn’t explain why someone wouldn’t ask for identification at the counter, as KIRO 7 News pointed out, highlighting the systemic issue.

An identity check does not have to rely on maintaining a ledger of records for many years or on a large database of data. Simply presenting identification or other supporting paperwork to a postal worker when submitting the form should be sufficient, as is the case with postal systems in other nations. Verify just their name, nothing more. Even while no system is flawless, it would be far more difficult to alter someone’s address without their consent if you could only take a quick look at their ID or other documents.

Otherwise, short of maintaining a constant degree of attention, there is little that anyone can do to stop this kind of scam. But eventually, the consumer shouldn’t have to bear the cost when the USPS could enforce the repair it purportedly corrected four years prior.

The previous executive informed me, “Everyone’s relying on the Post Office for elections and financial issues.” But he claimed he did not comprehend why the USPS was “not doing anything” about a straightforward but fatal problem that had an equally straightforward cure.